LLMaker

tl;dr:

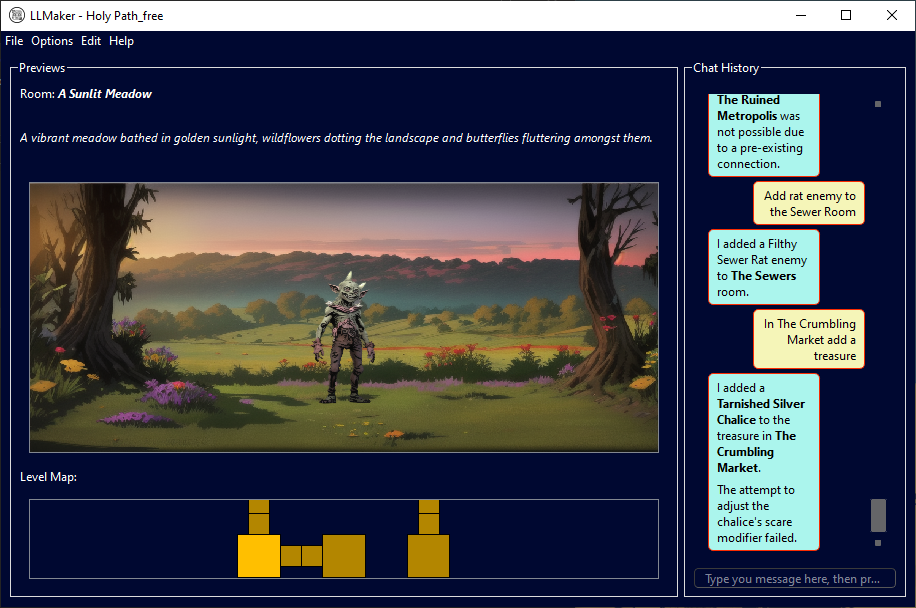

LLMaker is a mixed-initiative tool that lets users design video game levels for Dungeon Despair using large language models to parse edit commands and stable diffusion models to generate graphical assets.

LLMaking the LLMaker

LLMaker is my ongoing project for my PhD thesis focusing on the impact of using LLMs in mixed-initiative co-creation. It’s written in Python with PyQt6 for the GUI elements. Its releases can be installed on Windows, MacOS, and Debian-based Linux distros.

I started developing the application at the beginning of my PhD. LLMaker assists designers to create levels for the videogame Dungeon Despair, which I built alongside the application itself. The game is a reverse dungeon crawler inspired by Darkest Dungeon and built with pygame. The domain of Dungeon Despair is shared between the tool and the game itself, and is essentially a collection of PyDantic game objects and Python methods to manipulate them. These functions all have the @AILibFunction decorator from gptfunctionutil to be easily integrated in a tool calling pipeline.

In LLMaker, users are free to request edits to be made to the level (within domain constraints) or just ask questions about the level and converse with the LLM. The interface has a level minimap, an encounter preview, and a chat area.

The interaction loop is as follows:

- The user sends a message;

- The LLM processes the message and calls the right tools to execute the changes requested;

- The backend system updates the level accordingly;

- The LLM summarizes the changes back to the user;

- The interface is updated to reflect the level changes. If the change to the level cannot be completed, a functional error message is returned to the LLM, which can then either retry the change or just let the user know that the edit failed.

Each game object is defined by a name and a description, which are generated by the LLM conditioned by the user message and the current context. For example, if the current room is a swamp and the user asks for an enemy to be added, the LLM may generate a “Murky Goblin”. If the user asks for an enemy that does not fit with the theme, for example a fiery dragon, the LLM may try to include references to the swamp in the dragon’s description. Why does this matter? Because graphical assets (2D images) are generated using stable diffusion.

The textual information about the rooms and entities are used to condition the generation. The model currently implemented is a Stable Diffusion 1.5 model finetuned on RPG assets, and two different LoRAs are loaded to generate sprites and backdrops in the style of Darkest Dungeon. Using stable diffusion gives the user unrestricted creative freedom in terms of theme, settings, and game elements. Obviously, though, while the text itself may be fully unrestricted, the images themselves are restricted to the stable diffusion model.

Scale does not LLMatter

When I started working on this project, the choice of LLM was quite simple: either one of OpenAI’s GPT models, or a shitty local model. So GPT 3.5 Turbo it was.

However, while the model worked great, I was not a huge fan of the whole “scrape the whole internet to train our models” debacle. So much so that I wrote one section about it in the LLMs and Games survey paper, along with other ethical, political, and socio-ecological concerns the community had about training such large models.

So, after some time, I developed FREYR.

FREYR (a “Framework for Recognizing and Executing Your Requests”) is a simple framework preceding agentic LLM systems. When the user sends a message, a first LLM maps it to a sequence of intents. These intents are all possible actions that the system can make, and the option for chatting. Each intent is then processed by a different LLM that generates the parameters for the tool associated with the intent. Once all intents are processed and the level has been edited, a final LLM summarizes all changes to the level back to the user. If the user just wants to chat, another LLM simply generates the response.

The nice thing about this approach is that any LLM can play any role in the pipeline. This is particularly important since FREYR needs to update the game level via tool execution, which not all models support. Additionally, this allows designers to play on specific LLMs strengths: chatty LLMs fit great in the summary or conversation role, whereas more technical yet creative LLMs can work as tool operators.

In the end, I was using Gemma 2 9B for both intent detection and parameters generation, and Qwen 2.5 1.5B for summarization and conversation roles. These small-ish models could easily fit even on a consumer-level GPU, with total inference times (i.e.: time between the user sending a message and the user receiving a response) hovering around 3s to 6s, depending on the complexity of the request. The largest time bottlneck was still, however, the generation of graphics.

One shortcoming of FREYR was that the whole sequence breaks down horribly if the intents detected are wrong. While the tool execution was validated and reissued if there were problems (e.g.: missing parameters, invalid values, etc…), there was no control on the correctness of the intents detected. This problem is still present and could be resolved by having the LLM self-evaluate its detected intents, which would however increase inference times.

However, FREYR allowed me to not spend money on the OpenAI’s API, to have LLMaker run fully locally (I developed a simple Flask server API for self-hosting all the models needed), and much, much more control for the final user.

But we can go smaller still

You know what’s better than 9B models?

Well, in terms of size, 1B models.

In terms of accuracy, probably >9B models.

As I wrote above, one major limitation of the whole FREYR approach was that misidentifying designer intents had a cascade effect on the rest of the pipeline. I was reminded of what my professor at La Sapienza once said: “If your NLP model is 99% accurate, people will notice the 1% it fails.”

Boy, was he ever right.

When we had people play with LLMaker, most of the feedback we received was about how sometimes it would add one enemy instead of two, create rooms at random, or reply with a message without actually editing the level. When looking at the application logs, sure enough, misidentified intents were the culprits.

It was time to go smaller, and better. It was time for LLMaker-nano.

The goal of LLMaker-nano (github repo here) is simple: reduce inference time and hardware requirements by using small (1~3B) LLMs finetuned on examples collected by real users interactions.

And while we’re at it, I thought it’d be nice to generate sprites in a more custom style. As a Wizardry enthusiast, I pivoted to making a LoRA for Stable Diffusion XL to create images in the style of the famous Wizardry cards (you can find these on this website). The images had to be processed to remove both the “Wizardry” logo header, the monster name footer, and making all backgrounds the same color. After resizing them to the same size, headers and footers could be masked out with rectangles of the same color as the background (sampling the top-left-most pixel), then using the rembg library the background could be removed regardless of its color. The sprite was then saved on .jpg on a black background, which would be maintained by the LoRA.

For the language models, instead, I created two datasets: one for the intents, and one for the parameters to generate. These datasets were crafted by processing all application logs and extracting the user messages and the model’s detected intents and generated parameters. Guessing the right intent would improve user experience, and having the model natively generate (all) parameters in the right format would reduce retries, leading to lower inference times.

With some filtering and after manually correcting wrong intents, the two datasets comprised of 259 intents entries and 189 parameters generation entries.

Which is… not great. Too few to be able to get small models (like Gemma 3 2B) to generalize well enough.

For the intents, “conversation” was over-represented, so it would crop up in responsens randomly. Balancing intents lead to around 180 examples. While the model, in some cases, was performing slightly better than the 9B model, it was not the improvement I was hoping for.

Similarly, the parameter generation also had its fair share of issues, with the model learning to generate parameters for other tools in the same response. Annoying as it was, playing around with training parameters resulted in either not learning enough (thus generating ill-formed responses) or learning too much (thus generating the same-ish response for similar requests, ignoring nuances and killing creativity).

In short, no balance was found, and the project is currently on hold.

Not being allowed to release the LoRAs for the LLM nor the one for generating Wizardry sprites due to privacy and copyright concerns contributed to put this project on hold.

But one day, maybe, I could pick this back up.

The research bit

LLMaker has been developed as part of my PhD on the impact of using LLMs in mixed-initiative co-creation tools. I used LLMaker to explore whether users found easier to use traditional interfaces (buttons, sliders, menus, etc…) or natural-language interfaces (i.e.: a chat window), or an hybrid of the two. LLMaker was also used to measure perceived creativity not only for text generation, but also for images generated based on that text. Finally, a quasi-agentic pipeline was embedded in LLMaker, achieving performance comparable to large, proprietary models while running on consumer hardware and with smaller, local models.

Publications

@inproceedings{gallotta2024consistent, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Liapis, Antonios and Yannakakis, Georgios N.}, title = {Consistent Game Content Creation via Function Calling for Large Language Models}, year = {2024}, doi = {10.1109/CoG60054.2024.10645599}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Games (CoG)}, pages = {1-4} }

@inproceedings{gallotta2024llmaker, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Liapis, Antonios and Yannakakis, Georgios}, title = {LLMaker: A Game Level Design Interface Using (Only) Natural Language}, year = {2024}, doi = {10.1109/CoG60054.2024.10645626}, booktitle = {2024 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG)}, pages = {1-2}, }

@article{gallotta2025freyr, author = {Roberto Gallotta and Antonios Liapis and Georgios N. Yannakakis}, title = {FREYR: A Framework for Recognizing and Executing Your Requests}, year = {2025}, journal = {ArXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12423}, }

@inproceedings{gallotta2025importance, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Liapis, Antonios and Yannakakis, Georgios N.}, editor = {Machado, Penousal and Johnson, Colin and Santos, Iria}, title = {The Importance of Context in Image Generation: A Case Study for Video Game Sprites}, year = {2025}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-031-90167-6_5}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design (EvoMUSART) Conference}, pages = {66--81}, publisher = {Springer Nature Switzerland}, }