Space Engineers AI Spaceship Generator

tl;dr:

PCGSEPy is a Python library to visualize and evolve (via grammar evolution) spaceships for the videogame Space Engineers.

From atoms to spaceships

What is a spaceship?

In Space Engineers, luckily for me (and my research), it’s a bunch of voxels (i.e.: cubic pixel) welded together with hopes and dreams. Each voxel has its own unique ID, and some additional properties like position, orientation, and color.

Before fancy techniques like stable diffusion were a thing, creating structures made of voxels (or pixels, for that matter) with some level of controlability involved neural networks or other custom networks that, given for example a coordinate in space, woul tell you whether there was supposed to be a voxel (and which kind), or remain empty.

Or, like I decided to move forward with, you could define a grammar where each atom is one of the voxels’ ID and grow the structure from an initial state. The approach ended up being an L-system with turtle-like commands for placing voxels.

There are at least two benefits in using L-systems rather than other approaches such as a CPPN model. First, the L-system is fully explainable: each expansion rule is readable by a human, which is not the case for most black-box approaches. Second, since the structure is grown over multiple iterations, constraints such as voxels connectivity or avoiding self-intersections can be enforced by simply making sure the rules are sensible and reverting states when needed.

But a spaceship has a lot of voxels, you might think.

And you would be right. Writing rules on a voxel basis would take forever and surely lead to many, many errors.

That’s why the L-system was actually 2 L-systems: one low-level system defined how voxels formed tiles, and the other defined how these tiles could be combined together to create a spaceship. So, for example, a simple spaceship could be defined as cockpit-corridor-thrusters, where cockpit, corridor, and thrusters are the tiles, and cockpit is defined in the low-level L-system as block1x-block1x-...rotCW-block12x, where block1 is the ID of the voxel, x tells the turtle to move forward by 1 unit in the x direction, and rotCW tells the turtle to rotate 90deg clockwise.

This approach was further simplified by having a parametric L-system, where each atom had one or more parameters associated to it. So for example, rotCW became rot(cw,90) or rot(ccw,180) to rotate clockwise 90deg and counterclockwise 180deg, respectively. The same was also applied to the higher-level L-system, so for example corridor(4) meant having 4 corridor tiles in a sequence.

Rules of evolution and evolution of rules

What to do once all rules are defined? Make a spaceship, of course!

But based on what?

The goal of this project was to build something that users may like, so we scraped a good amount of spaceships built by users and uploaded on the Steam Workshop (with permission from GoodAI, the sister company of Keen Software, the developers of Space Engineers) that used the base-game blocks (no DLCs here). After analyzing these spaceships for main characteristics, we found three main metrics we could optimize for: symmetry, spaceship length along the main axis, and volume. And by “optimize”, I mean getting close to the average value of each of the metrics for human-authored spaceships.

Once we had metrics to optimize, it was easy to evolve spaceships by mutating the parameters of some of the atoms.

Starting from a collection of valid, simple spaceships, each spaceship was ranked on its fitness (aggregation of metrics), selected via fitness-proportional roulette-wheel selection, mutated the offsprings, and parents were kept as elites. Iterate over 200 or so generations, and you get… Space noodles.

But they’re good looking space noodles.

To make these noodles look more like spaceships, a convex hull was first generated using a predefined filling block. Once the full convex hull was formed, it was eroded to give the spaceship a more “organic” look. This was a tricky balancing act, but once the erosion was done, the spaceship blob was smoothed using slopes, half slopes, and 2x1 slopes blocks of the same material as the filling block.

At the end, you’d get a smooth, organic, spaceship blob thingy.

But it looked fine, and you could drive it. So that was good.

Anticipating users

The final bit of work was put all of this together into a single application where users would be able to choose the spaceship to evolve, and evolve it according to their preference.

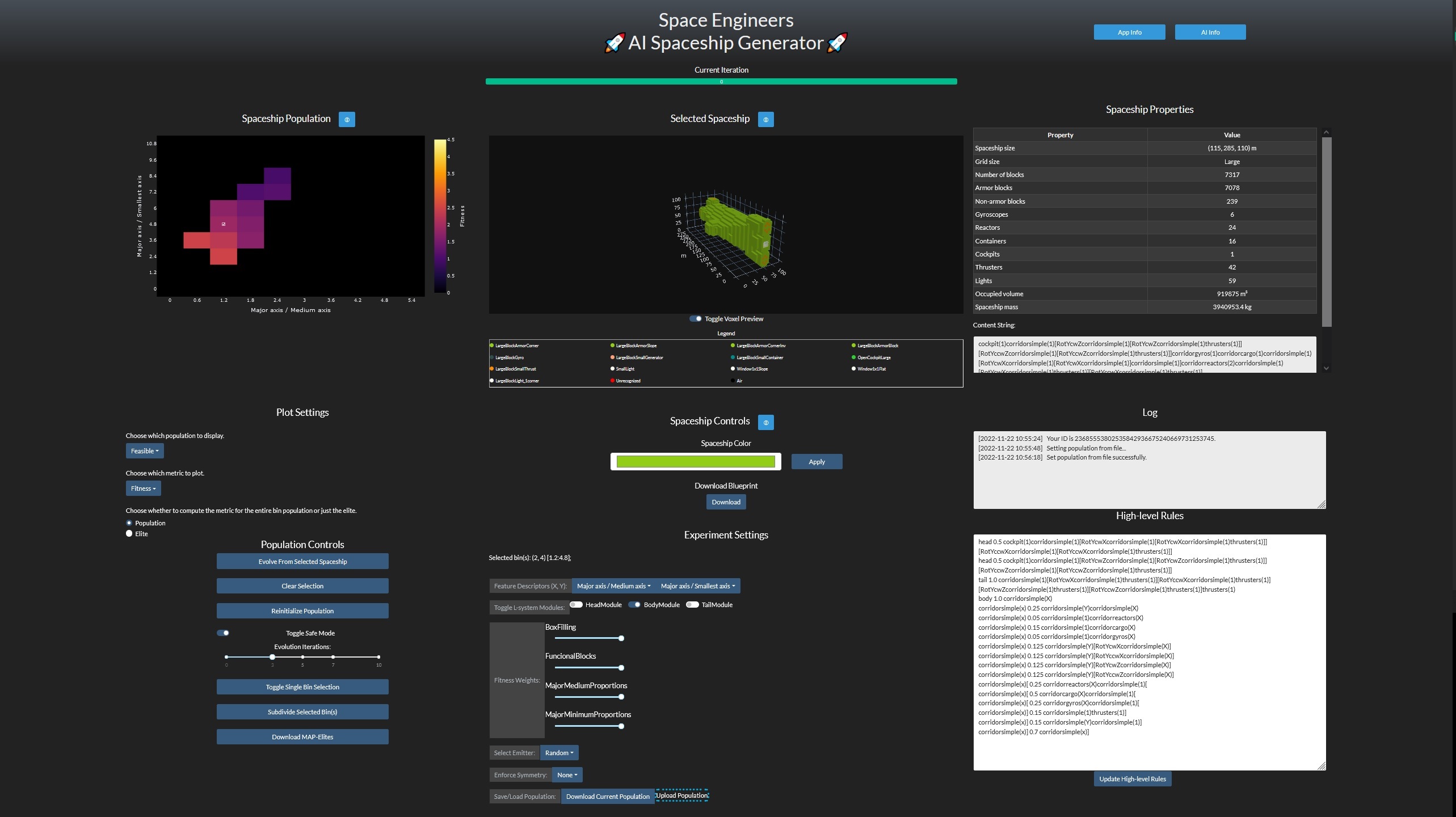

The solution was to maintain the “good” spaceships into a MAP-Elites archive (with the two axis relating to two phenotypical properties of the spaceship), and learn what the user liked based on which spaceships they chose to evolve next. This also had the benefit of reducing user fatigue: no user would happily choose a spaceship for 100, 200, 300 iterations without getting bored out of their mind.

So, the goal was clear: have an archive of solutions and shave away a few iterations by letting the system choose which spaceships to evolve based on the learned user preferences.

The archive was easy enough to make: it was a multi-strate archive (multiple spaceships per archive bin), and each bin in the archive could be subdivided up to a predefined number of times to allow for more granular selections. The best spaceship of the bin was displayed to the user, and neighboring bins were used as parents if the selected bin only had one spaceship.

The problem of learning user preferences was framed as a learnable custom emitter. An emitter is the method that decides which bin of the MAP-Elites archive should be selected to evolve next. To learn which bin should be picked next, the emitter was framed as a multi-armed bandit, with the human preference signal as learnable trajectory.

The web application developed to present the archive to the user and handle the interaction was built with Plotly Dash. Aside from the archive, it also contained a voxel preview and a breakdown of the properties of the selected spaceship, some controls for both the archive and the current spaceship, and an area where log messages were shown to the user. In a more advanced “developer” mode, the high- or low-level string that defined the spaceship could be edited manually, and different grammars or expansion rules could be uploaded to generate drastically different spaceship.

And of course, the currently selected spaceship could be downloaded as a “blueprint” file that could be loaded directly into Space Engineers, keeping all the block properties, including colors.

The Research Bit

The AI Spaceship Generator consists of several components, allowing it to generate both functional and aesthetically-pleasing spaceships for Space Engineers. The basis is a rule-based procedural content generation algorithm that generates working ships, which is combined with an evolutionary algorithm that optimises their appearance, resulting in a novel hybrid evolutionary algorithm. The basic heuristics for the evolutionary algorithm to optimise were derived by analysing the properties of spaceships available on the Space Engineers’ Steam Workshop page.

This is then combined with a novel algorithm that finds a diverse set of spaceships, making more choices available. Finally, we have built a graphical interface for these algorithms so that you can influence the spaceship generator’s choices, alongside another novel algorithm that tries to tune the system to better follow the your ideas.

Starting from an initial population of vessels, you can select a spaceship to “evolve” - the underlying evolutionary algorithm then “mutates” this, creating new spaceships with similar properties (shape, size, etc.). This process can be repeated to continuously generate new spaceships.

Publications

@inproceedings{gallotta2022evolving, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Arulkumaran, Kai and Soros, L. B.}, title = {Evolving spaceships with a hybrid L-system constrained optimisation evolutionary algorithm}, year = {2022}, publisher = {Association for Computing Machinery}, doi = {10.1145/3520304.3528775}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO) Companion}, pages = {711–714} }

@inproceedings{gallotta2022surrogate, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Arulkumaran, Kai and Soros, L. B.}, title = {Surrogate Infeasible Fitness Acquirement FI-2Pop for Procedural Content Generation}, year = {2022}, volume = {}, number = {}, doi = {10.1109/CoG51982.2022.9893592}, booktitle = {Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Games (CoG)}, pages = {500-503} }

@article{gallotta2024preferencelearning, author = {Gallotta, Roberto and Arulkumaran, Kai and Soros, L. B.}, title = {Preference-Learning Emitters for Mixed-Initiative Quality-Diversity Algorithms}, year = {2024}, journal = {IEEE Transactions on Games}, volume = {16}, number = {2}, doi = {10.1109/TG.2023.3264457}, pages = {303-316} }